March 31, 2025

Mains Article

31 Mar 2025

Context

- The recent fire brigade incident in Delhi, which led to the discovery of half-burnt currency notes at the residence of a High Court judge, has reignited concerns over judicial accountability in India.

- Therefore, it is important to critically examine the larger issue of transparency and integrity within the Indian judiciary, particularly focusing on the Collegium system of selecting judges.

- Moreover, it is crucial to discuss the need for reforms, and the proposal for an Indian Judicial Service (IJS) to address systemic inefficiencies.

A Persistent Concern Over Judicial Accountability

- The fire brigade incident, though shocking, is only one among several recent controversies that have cast a shadow on judicial credibility.

- The Supreme Court’s intervention in staying an insensitive verdict by a High Court judge regarding a minor’s sexual harassment case further exposes the lack of quality control in judicial appointments.

- Additionally, the Supreme Court's response to the Lokpal’s attempt to investigate corruption allegations against a judge underscores the judiciary’s resistance to external oversight.

- These instances collectively reflect a judicial system struggling to maintain accountability while remaining immune to public scrutiny.

Flaws in the Collegium System

- Lack of Transparency

- The selection and elevation of judges occur behind closed doors, with no formal records, criteria, or explanations made public.

- The decision-making process lacks objective standards, and the reasons behind selections or rejections are rarely disclosed.

- This opacity has led to speculation about favouritism, bias, and even corruption within the judicial selection process.

- The judiciary often declines to share the details of why certain candidates are selected over others, leading to a lack of public confidence.

- In contrast, other civil service appointments, such as the IAS and IPS, follow a structured and transparent selection process.

- Nepotism and Judicial Dynasties

- Since appointments are controlled by a small group of senior judges, there is a tendency to favour candidates who belong to influential legal families.

- This has led to the emergence of judicial dynasties, where judges' relatives are more likely to be selected over equally or more competent candidates from diverse backgrounds.

- This practice restricts the entry of talented individuals who do not have personal connections within the judiciary.

- Studies have shown that a significant number of High Court and Supreme Court judges come from families with a history in the judiciary or legal profession.

- This concentration of power limits opportunities for meritorious candidates from underprivileged backgrounds.

- Absence of Merit-Based Selection Criteria

- Unlike other professional recruitment processes, where clear eligibility criteria, examinations, and evaluations determine appointments, the Collegium system does not have a standardised, merit-based selection mechanism.

- There is no written test, interview panel, or structured assessment of a judge’s legal knowledge, ethical standards, or past judgments.

- As a result, the selection process often becomes subjective, favouring those with personal or professional proximity to the Collegium members.

- In the civil services, candidates undergo rigorous exams and interviews before being selected.

- However, in the Collegium system, judges are often chosen based on internal discussions with no formal assessment of their judicial competence, integrity, or decision-making abilities.

- Arbitrary Transfers and Promotions

- Another major flaw is the opaque system of judicial transfers and promotions.

- The Collegium decides which judges will be transferred from one High Court to another or elevated to the Supreme Court, but the reasons behind such decisions are rarely disclosed.

- This lack of accountability has led to suspicions that transfers may be influenced by favouritism, personal biases, or political considerations.

- In several instances, judges who delivered controversial verdicts or took strong stands against influential figures were transferred to other High Courts without any clear explanation.

- This raises concerns that transfers are sometimes used as a tool for controlling judges rather than ensuring efficiency in the judiciary.

- Resistance to External Oversight

- Despite the criticism, the judiciary has strongly resisted attempts to introduce external oversight mechanisms.

- The rejection of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) in 2015 is a prime example of this resistance.

- The NJAC was designed to make judicial appointments more accountable by involving representatives from both the judiciary and the executive.

- However, the Supreme Court struck it down, citing concerns over judicial independence.

- While independence is crucial, absolute autonomy without checks and balances can lead to an unaccountable system.

- Even when allegations of corruption or misconduct arise, the judiciary prefers internal inquiries, which are often perceived as biased or ineffective.

- In contrast, public officials in other branches of government are subject to investigations by independent bodies such as the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) and Lokpal.

- Lack of Diversity in the Higher Judiciary

- The Collegium system has also contributed to a lack of diversity in judicial appointments.

- Women, Dalits, Adivasis, and candidates from economically weaker backgrounds remain significantly underrepresented in the higher judiciary.

- This lack of inclusivity affects the credibility of the judiciary and limits perspectives in judicial decision-making.

- As of recent years, only a small percentage of Supreme Court and High Court judges are women, despite the increasing presence of women in the legal profession.

- Similarly, representation from marginalized communities remains disproportionately low.

The Case for an Indian Judicial Service (IJS)

- Diversity and Inclusivity: The current judiciary is dominated by a few elite families, with limited representation from marginalized communities and women. A nationwide examination would open doors for deserving candidates from all backgrounds.

- Merit-Based Selection: A structured, competitive recruitment process would ensure that judges are selected based on knowledge, competence, and ethical integrity rather than personal connections.

- Transparent Selection Process: Unlike the closed-door Collegium meetings, the IJS recruitment process would be conducted in a publicly accountable manner, reducing the scope for favouritism.

- Standardized Training: Newly appointed judges could undergo rigorous training in various branches of law, ensuring uniformity in judicial competence across different courts.

- Insulation from Executive Interference: The judiciary can still maintain its independence by formulating selection criteria while entrusting the recruitment process to an external, neutral body like the UPSC.

Conclusion

- The repeated controversies surrounding the judiciary indicate that judicial accountability and selection processes in India need urgent reforms.

- While the Collegium system has allowed the judiciary to remain independent, its lack of transparency has led to serious concerns about favouritism and inefficiency.

- The NJAC, though struck down, could be reconsidered with necessary safeguards to prevent executive overreach.

- More importantly, the establishment of an Indian Judicial Service could be a game-changing reform that ensures a fair, merit-based, and transparent process for judicial appointments.

Mains Article

31 Mar 2025

Context

- The introduction of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 was presented as a landmark reform in India's education system.

- However, beneath its promises of transformation, the policy masks deeper issues stemming from the government's approach to education.

- Over the last decade, the Union Government has consistently demonstrated an alarming indifference to the true needs of students and educators.

- This negligence is reflected in three primary areas: the centralisation of power, the commercialisation of education, and the communalisation of curricula.

Brazen Centralisation: A Threat to Federalism

- Increasing Centralisation

- One of the most concerning aspects of the Union Government’s education policy has been the increasing centralisation of decision-making.

- The Central Advisory Board of Education, which was supposed to ensure collaboration between the Union and State governments, has not met since September 2019.

- Despite implementing a major policy shift through NEP 2020, the government has not engaged in meaningful consultation with the states.

- This disregard for federal principles is particularly problematic because education is a subject under the Concurrent List of the Indian Constitution, meaning both the central and state governments have a role in shaping education policy.

- Heavy-Handed Approach

- Further evidence of this heavy-handed approach is seen in the PM-SHRI scheme, where the Union Government has allegedly withheld Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) funds to pressure states into compliance.

- These funds, crucial for implementing the Right to Education (RTE) Act, are being used as leverage to force state governments to align with central policies.

- The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education has even condemned this coercive tactic, calling for the unconditional release of SSA funds.

- Centralisation of Higher Education

- The centralisation of higher education governance is equally troubling.

- The draft University Grants Commission (UGC) guidelines for 2025 effectively strip state governments of their authority in appointing vice-chancellors in universities funded and operated by them.

- This shift in power toward the Union Government, facilitated through Governors who act as Chancellors, undermines the autonomy of state universities and threatens the federal structure of governance in education.

The Rise of Commercialisation: Education as a Privilege

- Privatisation of Schools

- Another major issue plaguing India’s education system is its growing commercialization.

- NEP 2020, while claiming to promote inclusive education, has in reality accelerated the privatisation of schools.

- The policy’s emphasis on ‘school complexes’ undermines the foundational principles of the Right to Education Act, which guarantees access to nearby primary and upper-primary schools.

- Instead of strengthening the public school system, the government has closed nearly 90,000 public schools since 2014 while allowing a sharp rise in private schools.

- This shift has disproportionately harmed the poor, forcing them into an expensive and often unregulated private education system.

- Privatisation of Higher Education

- In higher education, a similar trend is evident with the introduction of the Higher Education Financing Agency (HEFA).

- Replacing traditional block grants from the UGC, HEFA offers loans at market rates, which universities must repay using their own revenues, primarily student fees.

- The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education has reported that universities are increasingly burdened with repaying these loans through fee hikes, thereby shifting the financial strain onto students.

- This policy effectively turns higher education into a privilege accessible only to those who can afford it, eroding the principle of affordable public education.

- Moreover, the rise of financial corruption in educational institutions is closely tied to this commercialisation.

- Incidents such as bribery scandals in the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) and inefficiencies in the National Testing Agency (NTA) highlight the growing mismanagement and political interference in education governance.

Communalisation of Education: Rewriting History

- The third and perhaps most dangerous aspect of the current education policy is the ideological reshaping of curricula.

- The Government has made deliberate efforts to revise textbooks and syllabi to promote a particular historical and cultural narrative.

- The removal of references to Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination, Mughal history, and even the Preamble of the Indian Constitution from school textbooks is a clear indication of this trend.

- Public outrage eventually led to the reinstatement of the Preamble, but the larger pattern of historical revisionism remains a cause for concern.

- In higher education, the appointment of professors based on ideological alignment rather than academic merit has become widespread.

- Even prestigious institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) have seen leadership positions being filled by individuals with political affiliations rather than scholarly expertise.

- The UGC’s attempts to dilute qualification criteria for academic positions further reflect this effort to prioritise ideological conformity over educational excellence.

The Consequences and the Way Forward

- The combined effects of centralisation, commercialization, and communalization have had devastating consequences for students and educators in India.

- Public education has been systematically weakened, access to quality education has become more unequal, and the ideological tilt in curriculum threatens the integrity of academic discourse.

- To address these issues, it is crucial to restore financial and administrative autonomy to state governments in education policy, reinstate robust public funding for schools and universities, and ensure that curriculum changes are driven by academic expertise rather than political ideology.

- Additionally, greater transparency and accountability are needed to curb corruption in education administration.

Conclusion

- Education is not merely a tool for economic advancement but a fundamental pillar of democracy and social progress.

- If India’s education system continues down its current path, it risks deepening inequalities and undermining the nation’s intellectual and democratic foundations.

- The urgent need of the hour is to reclaim education as a public good, ensuring that it remains accessible, inclusive, and free from political and commercial manipulation.

Mains Article

31 Mar 2025

Why in the News?

The Labour Standing Committee of Parliament has pulled up the Union Labour Ministry for not convening the Indian Labour Conference (ILC) during the last 10 years.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- About Four Labour Codes (Context, Utility, etc.)

- Parliamentary Panel’s Report (Key Findings, Women’s Participation, Way Forward, etc.)

Background:

- India's labour regulatory landscape underwent a landmark transformation with the consolidation of 29 central labour laws into four comprehensive Labour Codes between 2019 and 2020.

- The move aimed to simplify the regulatory framework, improve ease of doing business, and ensure wider coverage of social and labour protections to workers across formal and informal sectors.

- Despite their passage in Parliament, these codes are yet to be fully operationalised due to delays in framing and implementing rules by States.

- A recent report by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Labour, Textiles, and Skill Development has urged the Ministry of Labour and Employment to expedite the process and also reconvene the long-pending Indian Labour Conference (ILC).

Overview of the Four Labour Codes:

- The Code on Wages, 2019

- This code amalgamates four existing laws related to wages, including the Minimum Wages Act and the Payment of Wages Act.

- It ensures universal minimum wage coverage across employment types and streamlines payment procedures.

- The Industrial Relations Code, 2020

- This code consolidates laws governing trade unions, industrial disputes, and conditions for layoffs and closures.

- It aims to create a balance between worker rights and employer flexibility and introduces provisions for fixed-term employment.

- The Social Security Code, 2020

- Covering various benefits such as provident fund, gratuity, maternity benefits, and health insurance, this code brings both organised and unorganised sector workers under a common social security net.

- It also enables the creation of social security funds for gig and platform workers.

- The Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020

- This code amalgamates 13 existing laws and addresses the safety, health, and welfare conditions of workers across different establishments.

- It includes provisions for working hours, welfare facilities, and appointment of safety officers.

Labour Code Implementation and Revival of Tripartite Dialogue:

- In its report tabled in Parliament, the committee highlighted delays and inconsistencies in the implementation of these labour codes.

- Progress on Rulemaking

- As of early 2024, 32 States and Union Territories had pre-published rules under all four codes. However, States like West Bengal and Lakshadweep had not done so.

- The committee noted that rule publication does not equate to enforcement and stressed the need for actual on-ground implementation, supported by administrative readiness and awareness drives.

- Tripartite Consultations and the Indian Labour Conference

- The committee criticised the Ministry for not holding the Indian Labour Conference (ILC) since 2015.

- The ILC is India’s primary platform for tripartite dialogue between government, employers, and worker unions.

- The committee argued that such a forum is vital, particularly during structural reforms like the rollout of the labour codes.

- Despite multiple requests by trade unions and stakeholders, the Ministry had not shared any timeline for the next ILC session.

- The committee emphasised that informal or bilateral consultations cannot replace the institutional significance of the ILC.

Women’s Participation in the Workforce:

- On a positive note, the committee highlighted the rising Worker Population Ratio (WPR) among women, citing data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS).

- Women's WPR rose from 28.7% in 2019–20 to 40.3% in 2023–24, a significant shift driven by policy interventions, digital job platforms, and increased awareness.

- To sustain and build on this trend, the panel recommended:

- Special employment outreach in rural, tribal, and underdeveloped areas

- Active promotion of the National Career Services (NCS) portal

- Greater efforts by industries to encourage female workforce participation through flexible work options

Way Forward:

- The committee’s report strongly advocated for:

- Expedited implementation of the four labour codes through close coordination with State governments

- Resumption of the Indian Labour Conference to ensure inclusive policymaking

- Capacity-building efforts for labour officials to ensure effective rule enforcement

- Data-driven monitoring mechanisms to evaluate the real-world impact of the labour reforms

- Given India’s rapidly changing employment landscape, marked by gig work, platform-based jobs, and informal labour, such reforms are critical to ensuring worker protection, job formalisation, and economic inclusivity.

Mains Article

31 Mar 2025

Why in News?

A new study, ‘Long-term impact and biological recovery in a deep-sea mining track’, published in Nature, reveals that a section of the Pacific Ocean seabed mined over 40 years ago has not yet recovered.

Conducted by scientists led by Britain’s National Oceanography Centre, the study found long-term sediment changes and a decline in larger marine organisms.

The findings come amid increasing calls for a moratorium on deep-sea mining. Recently, 36 countries attended a UN International Seabed Authority meeting in Jamaica to discuss whether mining companies should be permitted to extract metals from the ocean floor.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Deep Sea Mining

- Key Findings of the Study

- Deep-Sea Mining and Its Future

Deep Sea Mining

- Deep sea mining involves extracting mineral deposits and metals from the ocean’s seabed.

- It is classified into three types:

- Collecting polymetallic nodules from the ocean floor

- Mining massive seafloor sulphide deposits

- Stripping cobalt crusts from underwater rocks

- Significance of Deep Sea Mining

- These deposits contain valuable materials like nickel, rare earth elements, and cobalt, which are essential for renewable energy technologies, batteries, and everyday electronics such as cellphones and computers.

- Technological Developments in Deep Sea Mining

- The engineering methods for deep sea mining are still evolving. Companies are exploring:

- Vacuum-based extraction using massive pumps

- AI-driven deep-sea robots to selectively pick up nodules

- Advanced underwater machines to mine materials from underwater mountains and volcanoes

- The engineering methods for deep sea mining are still evolving. Companies are exploring:

- Strategic Importance

- Governments and companies see deep sea mining as crucial due to depleting onshore reserves and rising global demand for these critical materials.

Key Findings of the Study

- The study examined the long-term impact of a small-scale mining experiment conducted in 1979 on a section of the Pacific Ocean seafloor.

- The experiment involved removing polymetallic nodules, and scientists analyzed the affected 8-meter strip during an expedition in 2023.

- Key Findings

- Long-Term Environmental Impact: The mining led to lasting changes in the sediment and a decline in marine organism populations.

- Partial Recovery Observed: While some areas showed little to no recovery, certain animal groups were beginning to recolonize and repopulate.

- Broader Concerns About Deep Sea Mining

- Previous studies have warned about negative effects of deep sea mining below 200 meters, including:

- Harmful noise and vibrations

- Sediment plumes and light pollution

- A 2023 study in Current Biology found that deep sea mining significantly reduces animal populations and has a wider ecological impact than previously estimated.

- Previous studies have warned about negative effects of deep sea mining below 200 meters, including:

- Significance for Policy and Environmental Debate

- The study provides crucial data for assessing the long-term effects of deep-sea mining and guiding future regulations by the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

- Findings suggest that while some marine life begins to recover, full ecosystem restoration remains uncertain and may take decades.

- The research forms part of the Seabed Mining and Resilience to Experimental Impact (SMARTEX) project, which aims to support informed decision-making on deep-sea mining's societal and ecological implications.

Deep-Sea Mining and Its Future

- The Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is a vast, mineral-rich region in the Pacific Ocean, home to unique deep-sea biodiversity and crucial metal resources.

- CCZ is a vast plain in the North Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico.

- It is known to hold large volumes of polymetallic nodules containing minerals used in electric vehicles and solar panels including manganese, nickel, copper, and cobalt.

- Governments and companies are increasingly considering deep-sea mining to meet global demand for critical minerals needed in renewable energy and technology.

- The ISA is currently evaluating whether and under what conditions deep-sea mining should be permitted.

Mains Article

31 Mar 2025

Context:

- India has set an ambitious target to elevate its Textile and Apparel (T&A) exports from $34.8 billion in 2023-24 to $100 billion by 2030.

- However, achieving this goal requires transformative reforms in the sector.

Current Status of India's Textile and Apparel Exports:

- India's T&A exports have grown from $11.5 billion in FY2001 to $34.8 billion in FY24, holding only a 4% share in the global market.

- The apparel segment (HSN codes 61 and 62) constitutes 42% of total T&A exports.

- India's global apparel export share has stagnated at 3%, whereas competitors like Bangladesh and Vietnam have surged ahead.

- China’s global market share has declined from 34.8% to 29.8%, but India has not capitalized on this opportunity.

Key Challenges in the Textile Value Chain:

- Declining cotton production:

- India’s cotton production peaked at 39.8 million bales in 2013-14 but is projected to fall to 30 million bales in 2024-25, the lowest in 15 years.

- India is set to become a net importer of cotton, with imports reaching 2.6 million bales and exports dropping to 1.5 million bales.

- The ban on next-generation herbicide-tolerant (Ht) Bt cotton, despite Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC) approval, has hampered productivity.

- Disproportionate reliance on cotton over man-made fibres (MMFs):

- The global fibre consumption ratio is 30:70 (cotton to MMF), whereas in India, it is 60:40.

- High costs of MMF raw materials (polyester, viscose) in India (20% costlier than in Bangladesh, China, and Vietnam) reduce competitiveness.

- Structural and technological bottlenecks:

- Around 80% of India's 1 lakh garment factories operate in the decentralized sector, limiting scalability and technological adoption.

- Weak integration across the textile value chain restricts efficiency.

- Trade barriers and market access limitations:

- High import tariffs imposed by key markets -

- EU: 9.7%

- US: 11.47%

- Bangladesh enjoys zero-duty access to the EU under the “GSP Everything but Arms” arrangement.

- Vietnam benefits from a mere 1.66% tariff under the “EU-Vietnam FTA.”

- High import tariffs imposed by key markets -

Strategic Reforms for Achieving the $100 Billion Target:

- Promoting a fashion-driven industry:

- Incentivize MMF-based apparel production and remove non-tariff barriers such as Quality Control Orders (QCOs) on MMFs.

- Reduce raw material costs to improve competitiveness.

- Strengthening the PM-MITRA scheme:

- Fast-track the implementation of the Pradhan Mantri Mega Integrated Textile Region and Apparel (PM-MITRA) scheme.

- Enhance scalability and efficiency by promoting integrated textile hubs.

- Enhancing trade relations and market diversification:

- Negotiate Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with the EU and the US to reduce tariff disadvantages.

- Explore new markets such as Japan, Russia, Brazil, and South Korea, focusing on niche segments like women’s western wear and swimwear.

- Boosting cotton productivity and quality:

- Streamline GM crop approvals and establish a single-window clearance system for next-generation Bt cotton.

- Expand irrigation, promote high-density planting, and invest in precision farming to bridge productivity gaps with China (1,945 kg/hectare) and Brazil (1,839 kg/hectare).

Conclusion:

- India's goal of achieving $100 billion in T&A exports by 2030 is ambitious but not impossible.

- However, bold policy reforms and strategic interventions are necessary to enhance productivity, improve value chain integration, and secure competitive market access.

- Without these measures, the target will remain a distant dream.

Mains Article

31 Mar 2025

Why in news?

Adivasis in Jharkhand and the Chhotanagpur region will celebrate the Sarhul festival on April 1, 2025 to mark the new year and the arrival of spring.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Sarhul

- Sarhul: Three-day festival

- Sarhul’s Transformation Over The Years

- Significance of Sarhul

Sarhul

- Sarhul is the festival of the New Year celebrated in the state of Jharkhand by the tribal communities as part of the local Sarna religion.

- It is celebrated in the Hindu month of Chaitra, three days after the appearance of the new moon.

- It is also a celebration of the beginning of spring.

- Nature Worship in Sarhul

- Sarhul, meaning "worship of the Sal tree," is a significant Adivasi festival rooted in nature worship.

- The Sal tree is revered as the abode of Sama Maa, the village-protecting deity.

- Symbolic Union of Sun and Earth

- The festival symbolizes the union of the Sun and the Earth.

- A pahan (male priest) represents the Sun, while his wife (pahen) symbolizes the Earth, signifying the essential connection between sunlight and soil for sustaining life.

- Celebration of Life’s Cycle

- Sarhul marks the renewal of life.

- Only after its rituals are completed do Adivasis begin agricultural activities like ploughing, sowing, and forest gathering, emphasizing the festival’s deep ties to nature and sustenance.

- Sarhul Among Different Tribes

- Sarhul is celebrated by various tribes, including the Oraon, Munda, Santal, Khadia, and Ho, each with unique names and traditions associated with the festival.

- Evolution from Hunting to Agriculture

- Anthropologists noted that Sarhul originally centered around hunting but gradually evolved into an agriculture-based festival, reflecting the changing lifestyle of Adivasis in Chhotanagpur.

- Sarhul’s Journey Beyond Chhotanagpur

- In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Adivasi communities, including the Munda, Oraon, and Santal, carried Sarhul with them when they were sent as indentured laborers to distant lands.

- Today, Sarhul is celebrated from Assam’s tea gardens, to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan.

Sarhul: Three-day festival

- Sarhul is a three-day festival celebrated at Sarna Sthals, sacred groves near villages in Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and Bihar. These groves are central to the festival's rituals.

- Preparations and First Day

- Homes and Sarna Sthals are decorated with triangular red and white Sama flags.

- The pahan (priest) observes a fast, collects ceremonial water, and oversees the cleaning of houses and sacred sites. Sal flowers are gathered for rituals.

- Main Rituals on the Second Day

- The main ceremonies take place at the Sarna Sthal, where Sal flowers are offered to the deity and a rooster is sacrificed for prosperity and a good harvest.

- Holy water is sprinkled, and villagers perform traditional dances like Jadur, Gena, and Por Jadur.

- Young men also participate in ceremonial fishing and crab-catching.

- Final Day: Community Feast and Blessings

- The festival concludes with a grand community feast, where people share handia (rice beer) and traditional delicacies.

- The pahan blesses the villagers, marking the end of the celebrations.

Sarhul’s Transformation Over The Years

- In the 1960s, Adivasi leader Baba Karthik Oraon, a champion of social justice and tribal culture, initiated a Sarhul procession from Hatma to Siram Toli Sarna Sthal in Ranchi.

- Over the past 60 years, processions have become a central part of the festival, with Siram Toli emerging as a major gathering point.

- Political and Identity Assertion

- Sarhul has increasingly become a platform for Adivasi identity assertion.

- Some tribal groups use the festival to emphasize their distinctiveness from Hinduism, advocating for the inclusion of the Sarna religion in India's caste census.

- Debate Over Religious Identity

- While Sarna followers seek recognition as a separate religious group, other groups argue that Adivasis are part of Hinduism.

Significance of Sarhul

- Sarhul: A Festival Where Nature Takes Center Stage

- Unlike mainstream Indian festivals that celebrate human achievements, Sarhul Festival honors nature, with the Sal tree as its chief guest.

- A Festival Without Idols: Pure Worship of Nature

- Sarhul’s rituals are refreshingly simple—no idols or temple processions, just deep reverence for nature.

- Preserving Adivasi Heritage in a Changing World

- As urbanization threatens tribal traditions, Sarhul stands as a cultural movement reinforcing Adivasi identity.

- A Lesson for Modern Celebrations

- It teaches that true celebration lies in respecting nature, not in extravagance.

March 30, 2025

Mains Article

30 Mar 2025

Why in news?

The government has discontinued the Gold Monetisation Scheme’s medium- and long-term deposits from March 26, citing market conditions and scheme performance.

However, short-term deposits will continue at the discretion of banks based on commercial viability.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Gold Monetisation Scheme (GMS): An Overview

- Government and RBI on Gold Monetisation Scheme Closure

- Gold Mobilised Under the Gold Monetisation Scheme

- Status of Other Gold Schemes in India

Gold Monetisation Scheme (GMS): An Overview

- Introduced in November 2015, the GMS aimed to make idle gold productive by allowing individuals and institutions to sell or deposit gold with banks.

- The goal was to integrate gold into the formal economy, reduce gold imports, and lower the current account deficit.

- It was a revamped version of the earlier Gold Deposit Scheme.

- Key Features

- Allowed deposits from households, trusts, and institutions.

- Minimum deposit: 10 gm of raw gold (bars, coins, jewellery without stones/metals).

- No maximum deposit limit.

- Three Deposit Categories

- Short-term bank deposits (1-3 years) – Managed by banks.

- Medium-term government deposits (5-7 years) – Managed by the government.

- Long-term government deposits (12-15 years) – Managed by the government.

- Gold Monetisation Scheme: Interest Rates

- Short-Term Deposits

- Interest rates were determined by banks based on international lease rates, market conditions, and other costs.

- Interest was borne by the banks.

- Medium- and Long-Term Deposits

- Interest rates were set by the government in consultation with the RBI.

- Interest was paid by the Central government.

- Medium-term deposits (5-7 years):25% per annum

- Long-term deposits (12-15 years):5% per annum

- Short-Term Deposits

Government and RBI on Gold Monetisation Scheme Closure

- Discontinuation of the Scheme

- The Ministry of Finance announced the discontinuation of Medium- and Long-Term Government Deposits (MLTGD) under the GMS from March 26, 2025.

- Only short-term deposits managed by banks will continue.

- From March 26, 2025, no new deposits will be accepted at collection centers, testing agents, or designated bank branches.

- Impact on Existing Deposits

- Existing medium- and long-term deposits remain unaffected and will continue until maturity unless withdrawn prematurely.

- The RBI has not issued a separate release but has updated the scheme details on its website.

- RBI Guidelines

- The RBI will issue detailed guidelines regarding the scheme’s closure.

- It confirmed that the renewal of medium- and long-term deposits has been discontinued from March 26, 2025.

Gold Mobilised Under the Gold Monetisation Scheme

- Total Gold Collected - As of November 2024, a total of 31,164 kg of gold was mobilised under the scheme.

- Breakdown by Deposit Type

- Short-term deposits: 7,509 kg

- Medium-term deposits: 9,728 kg

- Long-term deposits: 13,926 kg

- Depositor Participation - Total depositors: 5,693

- Gold Collection from Different Sources

- From individuals/HUFs (FY 2016-17 & 2017-18): 1,134 kg

- From temples, trusts, mutual funds, gold ETFs, and firms: 10,872 kg

Status of Other Gold Schemes in India

- Gold Monetisation Scheme (GMS) Closure

- The GMS is the second gold-related scheme to be discontinued after the halt on sovereign gold bonds.

- The decision comes amid a sharp rise in gold prices, which increased by 41.5% from ₹63,920 per 10 gm (Jan 1, 2024) to ₹90,450 per 10 gm (March 25, 2025).

- Sovereign Gold Bonds (SGB) Discontinued

- The government stopped fresh issuance of sovereign gold bonds and did not announce any new tranche in Budget 2025-26.

- Reason: SGBs were considered a high-cost borrowing for the government.

- Government’s Gold Strategy

- Officials had earlier stated that SGBs aimed to boost gold investment, but the cut in gold import duty (Budget 2024-25) already aligned with this goal and helped increase demand.

Mains Article

30 Mar 2025

Why in the News?

In a report to Parliament, its Public Accounts Committee (PAC) has sought a comprehensive review of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) framework.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- PAC Report on GST (Context, Key Issues, Delays in Refunds, Suggestions, Way Forward)

Background:

- India's GST, introduced in 2017, was envisioned as a game-changer to unify India’s fragmented indirect tax system.

- However, nearly eight years later, a Parliamentary report has highlighted deep-rooted issues in GST implementation that impact businesses, State finances, and the overall efficiency of the tax system.

- The Public Accounts Committee (PAC), in its latest report to Parliament, has called for a comprehensive overhaul of the GST system, a “GST 2.0”, to reduce complexity, improve transparency, and enhance ease of compliance.

Compensation to States Remains a Key Concern:

- One of the biggest concerns flagged by the PAC is the lack of transparency and audit in the disbursal of GST compensation to States.

- The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) has not audited the GST Compensation Fund for over six years, reportedly due to the non-submission of proper financial data by the Ministry of Finance.

- This has hampered the release of compensation amounts to several States that heavily rely on these funds, especially industrial States like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, which feared revenue loss under GST.

- Further, a review of 10,667 cases showed 2,447 inconsistencies, and around ₹32,577 crore remains pending, underscoring the urgency for better fund management and auditing mechanisms.

Compliance Complexities and Technical Glitches:

- The PAC noted that several procedural inefficiencies continue to plague GST compliance, leading to either delayed revenue inflow to the government or cash flow constraints for businesses.

- Key issues include:

- Confusion over tax jurisdictions delaying refund.

- Unjustified cancellation of GST registrations: Of 14,998 cases studied, show-cause notices were not issued in 6,353 instances, violating legal norms

- Registration challenges: Taxpayers are not allowed to withdraw or modify applications, and in some cases, registrations were rejected without clear reasons

- Delays in Input Tax Credit (ITC) refunds, affecting MSMEs and exporters who rely on regular cash flows

- The Ministry claimed that some processes have been automated, but the Committee expressed concern over the lack of robust documentation and limited manual oversight, questioning the effectiveness of the automated systems.

Delays in Refunds and Their Economic Impact:

- The report specifically emphasised the inadequacy of the refund mechanism, with businesses experiencing long waiting periods, affecting working capital and daily operations, especially for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) and exporters.

- The Finance Ministry responded by promising improvements, including clearer timelines for refund processing and more real-time updates on the status of refund applications.

- The upcoming ‘Antarang Portal’ is expected to centralise filing, tracking, and documentation to enhance transparency.

Need for Institutional Reforms:

- The report also highlighted the absence of a functional GST Appellate Tribunal, causing legal bottlenecks and prolonged pendency in dispute resolution.

- As of March 2022, over 19,730 cases involving tax implications of ₹1.45 lakh crore were pending investigation.

- Legal experts argue that these unresolved cases, many of which have been pending for more than two years, hamper both compliance and business confidence.

Way Forward: Recommendations for GST 2.0

- Public Accounts Committee has recommended the government undertake a comprehensive stakeholder consultation to roll out GST 2.0, focusing on:

- Simplifying compliance by removing unnecessary procedures

- Ensuring timely audits and release of compensation to States

- Establishing the long-awaited GST Appellate Tribunal

- Improving digital platforms for registration, refunds, and returns

- Prioritising ITC refund processing, especially for MSMEs and exporters

- A tiered approach could be explored to allow differentiated compliance requirements for large corporates, mid-sized firms, and small traders to make the system more inclusive.

Conclusion:

GST was introduced as India’s biggest indirect tax reform, but implementation gaps and systemic inefficiencies have created avoidable hurdles for businesses and State governments alike.

While digital initiatives like the Antarang Portal and automation of notices are steps in the right direction, only a comprehensive revamp backed by regular audits, robust grievance redressal, and stakeholder consultation can unlock GST’s true potential.

Mains Article

30 Mar 2025

Why in News?

The India-US civil nuclear deal, signed two decades ago, has taken a significant step forward with regulatory approval from the US Department of Energy (DoE).

The approval allows US-based Holtec International to transfer Small Modular Reactor (SMR - a capacity of 30MWe to 300 MWe per unit) technology to Indian private firms.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Key Developments in the India-US Civil Nuclear Deal

- Conditions and Safeguards of the Recent Deal

- Strategic and Diplomatic Significance

- Geopolitical and Economic Factors

- Future Prospects

- India’s Strategic Vision for SMRs

- Conclusion

Key Developments in the India-US Civil Nuclear Deal:

- US DoE authorisation:

- Regulation involved: "10CFR810" (Part 810 of Title 10, US Atomic Energy Act, 1954).

- Authorised recipients:

- Holtec Asia (Holtec's Indian subsidiary).

- Tata Consulting Engineers Ltd (TCE).

- Larsen & Toubro Ltd (L&T).

- Excluded entities (pending Non-proliferation assurances):

- Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL).

- National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC).

- Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB).

Conditions and Safeguards of the Recent Deal:

- Duration: 10 years (subject to 5-year reviews).

- Restrictions:

- No retransfer of technology to other Indian entities or foreign countries without US consent.

- Use only for peaceful nuclear activities under International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards.

- No access to enrichment technology or Sensitive Nuclear Technology.

- Prohibition on military or naval propulsion use.

- Reporting requirements: Holtec to file quarterly reports to DoE.

Strategic and Diplomatic Significance:

- Revival of the 123 Civil Nuclear Agreement:

- The agreement, signed in 2007, aimed at full civil nuclear cooperation, including enrichment and reprocessing.

- Despite diplomatic progress, operational hurdles delayed implementation.

- India’s nuclear sector implications:

- Technological advancements:

- India’s civil nuclear programme has primarily relied on Pressurised Heavy Water Reactors (PHWRs).

- Holtec’s SMRs use Pressurised Water Reactor (PWR) technology, which dominates global nuclear energy.

- Opportunity to modernize India’s nuclear energy capabilities.

- Private sector involvement:

- Holtec’s collaboration with Indian firms could boost domestic manufacturing of SMR components.

- The potential to position India in the global SMR supply chain.

- Technological advancements:

Geopolitical and Economic Factors:

- US-India collaboration vs. China’s SMR expansion:

- China is aggressively expanding in the SMR domain, leveraging it for diplomatic influence in the Global South.

- India-US collaboration could provide a counterbalance to China’s dominance in nuclear technology.

- Impact on US-India trade relations: Despite protectionist policies under previous US administrations, this deal signifies a commitment to technology transfer and economic cooperation.

- Challenges in implementation:

- India’s Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (2010) has deterred foreign investment due to liability concerns.

- Amendments to the Atomic Energy Act (1962) needed to allow private sector participation in nuclear power generation.

Future Prospects:

- Next steps for Holtec in India - Possible collaborations:

- TCE for engineering expertise.

- L&T for manufacturing nuclear components.

- Potential entry of NPCIL and NTPC: Government may provide necessary assurances to include state-owned enterprises in future agreements.

- Holtec’s expansion plans: Holtec Asia’s facility in Dahej, Gujarat, could see workforce expansion if manufacturing is approved.

India’s Strategic Vision for SMRs:

- Clean energy transition: SMRs are seen as a viable option for reducing carbon emissions and meeting energy demands. Key part of India's renewable energy strategy.

- Global nuclear competitiveness: India’s engagement in SMR development could enhance its standing in the international nuclear energy market.

Conclusion:

The US regulatory approval for Holtec marks a milestone in operationalizing the India-US civil nuclear deal. This development aligns with India’s goals for energy security, technological advancement, and geopolitical positioning.

However, regulatory and legal challenges need resolution to fully leverage the deal’s potential.

Mains Article

30 Mar 2025

Why in news?

The Union government has notified the repatriation of Justice Yashwant Varma to the Allahabad High Court, following the Supreme Court Collegium’s recommendation.

His transfer comes amid allegations of charred currency notes being recovered from his residence after a fire, prompting Delhi High Court Chief Justice D.K. Upadhyaya to seek an in-house inquiry.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Transfer of High Court Judges: Constitutional Framework and Judicial Interpretation

- Criticisms of Judicial Transfers in India

- Striking Down of the NJAC: Reasons and Judicial Verdict

Transfer of High Court Judges: Constitutional Framework and Judicial Interpretation

- Article 222(1) of the Constitution empowers the President, in consultation with the Chief Justice of India (CJI), to transfer a judge from one High Court to another.

- Judicial Evolution of Transfer Process

- First Judges Case (1981): The Supreme Court held that the President's consultation with the CJI did not require concurrence, affirming the executive’s primacy in judicial transfers.

- Second Judges Case (1993): Overturned the earlier ruling, institutionalizing the collegium system and granting the CJI primacy in transfer decisions. The Court emphasized that transfers must serve the public interest and enhance judicial administration.

- Third Judges Case (1998): Further refined the collegium system, mandating consultation with the four seniormost judges and seeking inputs from Supreme Court judges familiar with the concerned High Court.

- Process of Transfer

- The collegium recommends the transfer.

- The Law Minister reviews and advises the Prime Minister.

- The Prime Minister forwards the recommendation to the President.

- Upon presidential approval, the transfer is formalized through a gazette notification.

- Key Considerations

- The CJI must consult relevant judges and legal experts to prevent arbitrariness.

- A judge’s consent is not required for transfer.

- Judicial review of transfer decisions is limited to prevent external interference.

Criticisms of Judicial Transfers in India

- Concerns Over Judicial Independence

- The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) has raised concerns about increasing executive interference in judicial appointments and transfers, undermining judicial independence.

- Lack of Transparency and Accountability

- Judicial transfers, often carried out without the affected judge’s consent, are justified on vague grounds like “public interest” and “better administration of justice.”

- This ambiguity makes it difficult to differentiate between legitimate and punitive transfers.

- Recommendations for Reform

- The ICJ has suggested the establishment of a Judicial Council to oversee appointments and transfers based on transparent, objective, and predetermined criteria.

- It recommends that the council be composed mainly of judges, aligning with international standards of judicial independence.

Striking Down of the NJAC: Reasons and Judicial Verdict

- In 2014, the then government introduced the 99th Constitutional Amendment and the NJAC Act to replace the opaque collegium system for judicial appointments.

- The NJAC was designed as an independent body to appoint Supreme Court and High Court judges.

- Composition of the NJAC

- The NJAC was to be chaired by the CJI and included:

- Two senior-most Supreme Court judges

- Union Law Minister

- Two eminent civil society members (one from SC/ST/OBC or a woman). These members were nominated by a panel consisting of the CJI, Prime Minister, and Leader of the Opposition.

- The NJAC was to be chaired by the CJI and included:

- Political and Legal Challenges

- The amendment passed almost unanimously in Parliament and was ratified by 16 State legislatures.

- However, it was challenged in the Supreme Court, with critics arguing that the veto power granted to any two NJAC members—potentially including the Law Minister—could undermine judicial independence.

- Supreme Court Verdict (2015)

- In October 2015, a five-judge Bench ruled (4:1) that the NJAC was unconstitutional, stating that it violated the basic structure of the Constitution, particularly judicial independence.

- The majority held that the Law Minister and non-judicial members could interfere with judicial appointments, compromising autonomy.

- Dissenting opinion by Justice Jasti Chelameswar: He criticized the collegium’s lack of transparency, arguing that NJAC could have prevented "unwholesome trade-offs" and "incestuous accommodations" between the judiciary and executive.

- The verdict restored the collegium system, reinforcing the judiciary’s primacy in appointments but leaving concerns over transparency unresolved.

March 29, 2025

Mains Article

29 Mar 2025

Why in the News?

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture has criticised the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) for the persistent existence of accident-prone “black spots” on national highways (NHs).

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Background (Context, About Black Spots)

- Parliamentary Panel’s Report (Key Findings, Action Plan, Audits, Targets vs Actuals, etc.)

Background:

- India has one of the highest numbers of road accidents in the world.

- A significant portion of these fatalities happen on national highways (NHs) due to poorly designed or managed road segments called “black spots”, specific locations where a high number of accidents and fatalities have been recorded over the years.

- Despite various efforts by the MoRTH to reduce road deaths, a recent report by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture reveals worrying gaps in execution.

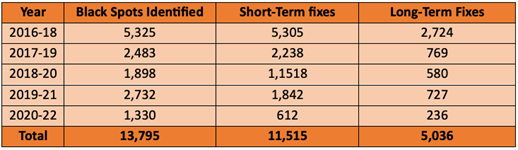

- According to MoRTH’s own data, out of 13,795 black spots identified across India’s NHs, long-term rectification has been completed on only 5,036 spots.

- This translates to a large number of dangerous zones still unaddressed, posing daily risks to drivers and pedestrians.

About Black Spots:

- A “black spot” is a hazardous location on a national highway identified by the frequency and severity of road accidents, particularly those causing grievous injuries or deaths across three consecutive years.

- These spots can occur due to poor road design, lack of signage, bad lighting, sharp curves, or congested junctions.

Parliamentary Panel’s Findings: A Governance Failure

- In a report related to the Demands for Grants for FY 2025-26, the parliamentary panel called the poor progress a “significant governance failure”.

- It emphasised that these black spots represent preventable dangers that could be fixed with faster, coordinated intervention.

- The committee expressed deep concern about the mismatch between the ministry’s commitments and the reality on the ground.

Three-Tier Action Plan for Fixing Black Spots:

- To address the issue, the panel has recommended a three-tier prioritisation framework based on:

- Severity (how often and how serious the accidents are),

- Complexity of the fix required, and

- Population exposure (how many people use the spot regularly).

- The plan includes strict time-bound interventions:

- Category A black spots (highest risk):

- Temporary safety measures must be deployed immediately.

- Permanent rectification must begin within 30 days of identification.

- Category B black spots (moderate risk):

- Must be fixed within 90 days.

- Category C black spots (lower priority):

- Deadline of 180 days.

- Agencies that fail to meet the timelines should face penalties.

- Category A black spots (highest risk):

Need for Post-Implementation Audits:

- The panel didn’t just focus on fixing black spots, it also highlighted the importance of follow-up.

It recommended that safety audits be carried out at 3-month and 12-month intervals after rectification to ensure the solutions actually work. - To promote accountability, the panel suggested creating a public dashboard that would show the status of each black spot, the progress of rectification, and the responsible implementing agency.

MoRTH’s Targets and Reality:

- The ministry has set an ambitious goal to reduce road fatalities by 95% by 2028.

- As part of this, it has committed to fixing 1,000 black spots in FY 2025–26 and eliminating all identified black spots by FY 2027-28 through better signage, road design, and junction management.

- However, the numbers so far reflect a lag in long-term fixes:

- Short-term solutions (like installing signage, speed breakers, or barriers) are often implemented, but long-term structural fixes, such as underpasses, road widening, or redesign—remain slow.

Conclusion:

Fixing black spots on national highways isn’t just a technical challenge, it’s a matter of saving lives. The current pace of work is not in sync with the ministry’s stated ambitions.

The parliamentary panel’s recommendations provide a clear and actionable path forward, focusing on urgency, accountability, and transparency.

To truly make Indian roads safer, quick identification must be followed by equally fast execution, because behind every black spot, there’s a life that can be saved.

Mains Article

29 Mar 2025

Context

- The global energy landscape has undergone significant transformations in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war.

- As African nations strive to diversify their energy sources, nuclear power is emerging as a critical component of their energy transition.

- However, this shift has also attracted the attention of global powers eager to secure a stake in Africa’s nuclear market.

- China, in particular, has positioned itself as the dominant player, challenging traditional Western influence and raising concerns about geopolitical dependencies.

Africa’s Nuclear Energy Aspirations

- Currently, Africa has only one operational nuclear power plant, the Koeberg Nuclear Power Station in South Africa, which was built by a French consortium.

- However, several African countries, including Ghana, Nigeria, Sudan, Rwanda, Kenya, and Zambia, are actively planning to incorporate nuclear energy into their national power grids.

- Projections suggest that Africa could generate up to 15,000 MW of nuclear energy by 2035, representing a significant opportunity for investment, estimated at $105 billion.

- The potential for nuclear energy in Africa is not only an economic opportunity but also a solution to the continent’s chronic electricity shortages and unreliable power supply.

The Scramble for Africa’s Nuclear Market

- Historically, France dominated Africa’s nuclear market, particularly in Francophone nations.

- However, France’s influence is waning as other global powers aggressively pursue nuclear partnerships in Africa.

- The United States, through the US-Africa Nuclear Energy Summit (USANES), has sought to establish itself as a major player.

- However, the future of U.S. involvement depends on the political direction of President Donald Trump’s administration.

- Russia, another key contender, has signed multiple nuclear agreements with African nations, including Egypt, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Burundi.

- The Russian state-owned nuclear corporation, Rosatom, has been constructing a reactor in El Dabaa, Egypt, since 2022, albeit with slow progress.

- South Korea, through Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power (KHNP), has also shown interest in Africa’s nuclear market.

- However, it is China that has emerged as the most influential and aggressive investor in African nuclear energy.

China’s Dominance in Africa’s Nuclear Expansion

- Recent but Rapidly Expanding

- In 2012, the China Atomic Energy Authority launched a scholarship program in collaboration with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to train African and South Asian students in nuclear science.

- This initiative strategically familiarised African nations with Chinese nuclear technologies and procedures, increasing the likelihood of future partnerships.

- Today, China operates more than 50 nuclear reactors, reinforcing its status as a global nuclear power.

- Growing MoUs

- Two state-owned enterprises, the China General Nuclear Power Group (CGN) and the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), are spearheading China’s nuclear expansion in Africa.

- In 2024, during the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing, Nigeria signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with China for the design, construction, and maintenance of nuclear power plants.

- Similarly, Uganda signed an MoU with China to build a 2 GW nuclear power plant, with the first unit expected to be operational by 2031.

- Kenya, while still undecided on its nuclear partner, plans to have a research reactor by 2030.

- Meanwhile, Ghana has opted for U.S.-based NuScale Power and Regnum Technology Group to develop its Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), while China National Nuclear Corporation will construct a Large Reactor (LR).

- Diminishing Influence of Russia

- In West Africa, pro-Russian governments in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali have signed nuclear cooperation agreements with Rosatom.

- However, Russia’s economic challenges, exacerbated by sanctions due to the Ukraine war, may hinder its ability to make large-scale investments in African nuclear projects.

- This could push these nations toward China, which is better positioned to provide financial and technical support.

The Impact on India’s Energy Security

- Africa’s nuclear ambitions have broader implications for global energy security, particularly for India.

- As India aims to increase its nuclear power capacity from 8,180 MW to 100 GW by 2047, securing uranium supplies will be crucial.

- India has previously signed a civil nuclear cooperation agreement with Namibia and is exploring uranium mining projects in Niger and Namibia.

- However, China’s growing influence in Africa’s nuclear sector could pose challenges for India’s energy security by limiting its access to uranium and nuclear-related infrastructure.

- Furthermore, many African countries lack the transmission networks necessary to distribute power from nuclear plants.

- China, through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has the capability to develop these networks, further cementing its dominance in Africa’s clean energy market.

- If China successfully integrates nuclear power with its broader infrastructure projects, it will not only strengthen its position in Africa but also gain greater geopolitical leverage over nations dependent on its investments.

Conclusion

- Africa’s shift toward nuclear energy presents both opportunities and challenges.

- While nuclear power can provide a stable and reliable source of electricity, the sector has become a battleground for global powers seeking to expand their geopolitical influence.

- China has emerged as the dominant force in Africa’s nuclear market, outpacing traditional players like France, the U.S., and Russia.

- This growing Chinese influence raises concerns about economic dependencies and strategic vulnerabilities for African nations.

Mains Article

29 Mar 2025

Context

- India has historically been an influential global player, balancing economic growth with diplomatic relations.

- However, recent geopolitical shifts have raised concerns about India’s limited role in resolving international conflicts.

- While India has taken decisive action in regional crises, such as its interventions in Bangladesh (1971), the Maldives (1988), and Sri Lanka (2009), it has recently adopted a cautious stance.

- The question arises: should India be more proactive in global geopolitics? Experts argue that India must recalibrate its foreign policy, balancing economic ambitions with strategic engagement to secure its position as a major global power.

India’s Historical and Current Diplomatic Approach

- India’s leadership in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) reflected its early commitment to shaping global politics.

- In contrast, its current multi-alignment strategy prioritises bilateral ties over collective geopolitical influence.

- India has made significant contributions to global welfare through initiatives like ‘Vaccine Maitri,’ climate action, and humanitarian aid.

- However, its reluctance to actively engage in major conflicts, such as the Russia-Ukraine war or the Israel-Palestine crisis, raises questions about its long-term vision as a global power.

- Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s diplomatic outreach to Russia and Ukraine has been commendable, but India has largely remained a bystander in peace negotiations.

- Its abstention from UNSC votes on the Ukraine war influenced developing nations, yet India has not capitalised on its unique position to mediate effectively.

- Given its economic and diplomatic credibility, should India not aspire for a seat at the “high table” of global conflict resolution?

The Risks of Remaining Passive

- Ceding Influence to Emerging Middle Powers

- In the absence of Indian leadership, other nations are stepping in to fill the diplomatic vacuum.

- Countries like Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have taken on active mediation roles in various conflicts, thereby expanding their geopolitical influence.

- Türkiye’s Role in the Ukraine-Russia Conflict

- Türkiye hosted direct negotiations between Ukraine and Russia in 2022, demonstrating its ability to mediate in European conflicts.

- This enhanced Türkiye’s credibility as a neutral broker and strengthened its diplomatic standing.

- Saudi Arabia’s Multi-Alignment Strategy

- Saudi Arabia recently hosted high-profile U.S.-Russia and U.S.-Ukraine negotiations, positioning itself as a major diplomatic force.

- It is leveraging its oil wealth and strategic location to assert itself as a key player in global geopolitics.

- Qatar’s Mediation in Africa: Qatar successfully facilitated a ceasefire between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, proving that small but influential states can play a major role in global conflict resolution.

- If India does not step up, it risks falling behind these emerging middle powers in diplomatic influence.

- By playing an active role, India could shape discussions on global security rather than merely reacting to them.

- Diminishing Credibility as a Global Leader

- India has often projected itself as the leader of the Global South, advocating for the interests of developing nations.

- However, if it remains hesitant to engage in conflict resolution, it may lose credibility in the eyes of its allies.

- Expectations from a Rising Power

- India, as the world’s fifth-largest economy and an aspiring permanent member of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), is expected to contribute more than just statements.

- If India seeks a leadership role in global governance, it cannot afford to be perceived as indifferent to global crises.

- Implications for UNSC Aspirations

- India argues that UNSC decisions lack legitimacy without the world’s largest democracy.

- However, this argument weakens if India is unwilling to take decisive action in global affairs outside the UNSC framework.

- The ‘Not an Era of War’ Doctrine

- Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s statement to Vladimir Putin that ‘this is not an era of war’ was widely appreciated.

- However, beyond rhetoric, India has not taken concrete steps to push for peace.

- If India remains passive, such statements may be seen as diplomatic posturing rather than genuine efforts at conflict resolution.

- Strategic Setbacks in a Shifting Global Order

- The global balance of power is shifting, with increasing geopolitical fragmentation.

- If India does not actively engage, it may find itself left out of crucial negotiations that could shape the future world order.

- U.S.-China ‘Deal’ and the Risk of Regional Marginalisation

- As tensions between the U.S. and China evolve, there is a possibility of a new understanding between the two superpowers, dividing regions into spheres of influence.

- If India does not assert itself, it could be excluded from key geopolitical arrangements in Asia.

- As tensions between the U.S. and China evolve, there is a possibility of a new understanding between the two superpowers, dividing regions into spheres of influence.

- Threat to the Quad’s Relevance

- The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), consisting of India, the U.S., Japan, and Australia, is meant to counterbalance China’s influence.

- However, if India remains hesitant to engage more proactively, the Quad itself could lose its strategic significance, weakening India’s position in the Indo-Pacific.

- The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), consisting of India, the U.S., Japan, and Australia, is meant to counterbalance China’s influence.

- China’s Expanding Influence

- China’s growing presence in Africa, Latin America, and South Asia through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is reshaping global geopolitics.

- While India has expressed concerns over China’s economic and strategic expansion, its passive approach limits its ability to counterbalance Chinese influence effectively.

- China’s growing presence in Africa, Latin America, and South Asia through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is reshaping global geopolitics.

The Way Ahead for India to Establish Itself as a Key Geopolitical Player

- Strengthening Regional Policies

- India’s bilateral relations in West Asia, Central Asia, and East Asia must be supplemented with active participation in regional frameworks.

- While India has maintained strong ties with Central Asian nations, its reduced engagement in the SCO limits its influence in the region.

- Similarly, after opting out of RCEP, India must find alternative ways to strengthen economic ties with East Asian nations.

- Deepening Ties with Europe

- With Europe facing internal and external pressures, India has a strategic opportunity to enhance its presence in the region.

- A trade agreement with the U.S. could serve as a foundation for deeper economic and political collaboration with the European Union.

- Playing a More Proactive Role in Conflict Resolution

- India does not need to position itself as a mediator but should be ready to facilitate dialogue and negotiations.

- Its past role in the Korean War (1951-52) and its recent diplomatic efforts in the UNSC (2021-22) show that India can bridge divergent geopolitical interests.

Conclusion

- India’s ambition to be a global power must go beyond economic growth; it must also involve strategic geopolitical engagement.

- The world is undergoing a structural shift, with rising unilateralism and realignments in global politics.

- By proactively shaping global events rather than reacting to them, India can strengthen its influence and secure its place as a key pole in a multipolar world.

- As the international order evolves, India’s leadership will be judged not only by its economic prowess but also by its willingness to shape a stable and balanced global landscape.

Mains Article

29 Mar 2025

Context:

- India, once a leading producer and exporter of cotton, is now facing a severe decline in production and has become a net importer of the natural fibre.

- The crisis is largely due to policy paralysis and restrictions on genetically modified (GM) crops rather than external factors.

The Rise of India's Cotton Production:

- Technological advancements: India became a major cotton producer due to hybrid technology and later, genetically modified (GM) Bt cotton.

- GM cotton revolution:

- 1970: H-4, the world’s first cotton hybrid, developed by C.T. Patel.

- 1972: Varalaxmi, the first interspecific cotton hybrid, developed by B.H. Katarki.

- 2002-03: Introduction of GM Bt cotton, which offered resistance against the American bollworm.

- 2006: Bollgard-II technology introduced, providing additional protection against pests.

- 2013-14: 95% of India's cotton cultivation adopted Bt cotton, pushing yield to a peak of 566 kg per hectare.

The Decline in Cotton Production:

- Production trends:

- 2002-03 to 2013-14: Production surged from 13.6 million bales (mb, 1 bale=170 kg) to 39.8 mb. The imports halved to 1.1 mb and exports surged well over hundredfold to 11.6 mb (from not even 0.1 mb in 2002-03).

- 2024-25: Projected at 29.5 mb, the lowest since 2008-09.

- Imports surpassing exports: 3 mb imports vs. 1.7 mb exports.

- Reasons for decline:

- Policy restrictions on GM technology and regulatory hurdles. For example, the treatment of GM crops as “hazardous substances” under the Environment Protection Act, 1986.

- Resistance to scientific advancements in agriculture.

- Pink bollworm infestation due to lack of new pest-resistant varieties.

Regulatory and Policy Failures:

- Ban on GM crops:

- 2010: Moratorium on GM Bt brinjal, setting a precedent for halting GM crop approvals.

- Field trials of new GM cotton hybrids blocked under the NDA government.

- Regulatory deadlock despite scientific validation and biosafety data.

- Judicial and activist interventions:

- Activist-driven opposition led to stagnation in agricultural biotech research.

- Courts stepping into technical domains have further slowed progress.

Economic Implications:

- Impact on trade:

- A country that was the world’s no. 1 producer in 2015-16 and a close second biggest exporter to the US by 2011-12 has today been “inundated” by American, Australian, Egyptian and Brazilian cotton.

- Cotton imports doubled in value in 2024-25 compared to the previous year (from $518.4 million to $1,040.4 million) alongside a dip in exports (from $729.4 million to $660.5 million).

- Pressure from the US and Brazil to remove the 11% import duty on cotton.

- Impact on farmers:

- Indian farmers are denied access to the latest GM technologies.

- Despite resistance to GM crops, GM soyameal and corn are being imported.

Need for Policy Reforms:

- Scientific approach over activism: Policy decisions should be based on scientific validation rather than public consultations dominated by activists.

- Revival of GM research: Approval of new pest-resistant GM cotton varieties. Establishment of a transparent and evidence-based regulatory framework.

- Reducing import dependence: Encouraging domestic production through technology adoption. Balancing environmental concerns with the need for agricultural progress.

Conclusion:

- In 1853, Karl Marx famously wrote how British rule “broke up the Indian handloom and destroyed the spinning wheel”, and finally “inundated the very mother country of cotton with cottons”.

- Something similar has taken place with Indian cotton over the last decade. However, it was not by any grand imperialist design, but by sheer domestic policy paralysis and ineptitude.

- India’s cotton crisis underscores the urgent need for a balanced, science-driven approach to agricultural policy.

- The failure to act decisively has not only hurt farmers but also made India reliant on foreign cotton, benefiting global competitors like the US and Brazil.

Mains Article

29 Mar 2025

Why in News?

The discovery of large sums of cash at the residence of Delhi High Court judge Justice Yashwant Varma has raised concerns about corruption in India’s higher judiciary.

This incident has strengthened calls for public disclosure of judges’ assets and liabilities, which, unlike other public servants, they are not obligated to reveal—and most have not done so.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Supreme Court’s Position on Judges’ Asset Disclosure

- Situation in High Courts Regarding Judges’ Asset Disclosure

- Public Servants and Asset Disclosure

Supreme Court’s Position on Judges’ Asset Disclosure

- 1997 Resolution

- In 1997, under then CJI J S Verma, the Supreme Court adopted a resolution requiring judges to declare their assets, including those of their spouses and dependents, to the Chief Justice.

- However, this did not mandate public disclosure.

- 2009 Resolution

- In September 2009, the SC full Bench decided to publish judges' asset declarations on its website, but only on a voluntary basis.

- These disclosures appeared in November 2009, and some High Courts followed suit.

- Lack of Updates Since 2018

- The SC website has not been updated since 2018.

- It only lists the judges who have submitted declarations to the CJI without publishing the actual disclosures.

- Former judges’ declarations have also been removed.

- 2019 RTI Case and SC Ruling

- In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that judges' assets and liabilities do not qualify as “personal information.”

- This case originated from an RTI request filed in 2009 by an activist to verify if SC judges had disclosed their assets as per the 1997 resolution.

Situation in High Courts Regarding Judges’ Asset Disclosure

- Low Compliance with Public Disclosure

- As of March 1, 2024, only 97 out of 770 High Court judges (less than 13%) have publicly declared their assets.

- These judges belong to seven High Courts: Delhi, Punjab & Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Madras, Chhattisgarh, Kerala, and Karnataka.

- Most High Courts oppose public disclosure.

- Resistance from High Courts

- In 2012, the Uttarakhand High Court passed a resolution strongly objecting to judges’ asset disclosure under the RTI Act.

- The Allahabad High Court rejected an RTI request for judges' asset details, claiming it was outside the RTI Act’s scope.

- Similar denials came from Rajasthan, Bombay, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Gauhati, and Sikkim High Courts.

- Parliamentary Committee’s Recommendation

- In 2023, Parliament’s Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, and Law and Justice recommended a law mandating the disclosure of Supreme Court and High Court judges’ assets.

- However, no legislative action has been taken so far.

Public Servants and Asset Disclosure

- Mandatory Asset Declarations

- Unlike judges, most public servants are required to declare their assets, with this information often being publicly accessible.

- The RTI Act of 2005 has played a crucial role in ensuring transparency and accountability in government operations.

- RTI’s Role in Public Disclosure

- Government officials must annually declare their assets to their respective cadre-controlling authorities, and in most cases, these details are available in the public domain.

- Several states, including Gujarat, Kerala, and Madhya Pradesh, have strict provisions mandating asset declarations by bureaucrats, which can be accessed through RTI applications.

- Ministers and MPs

- Since 2009, it has become standard practice for Union Ministers, including the Prime Minister, to submit asset declarations to the PMO, which are accessible via its website.

- Many state governments have followed this practice.