Why in news?

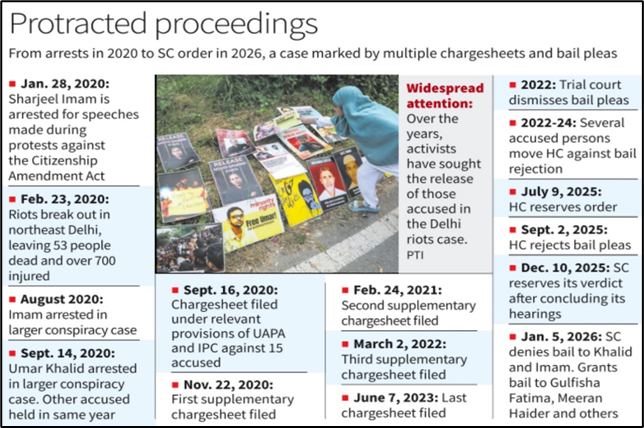

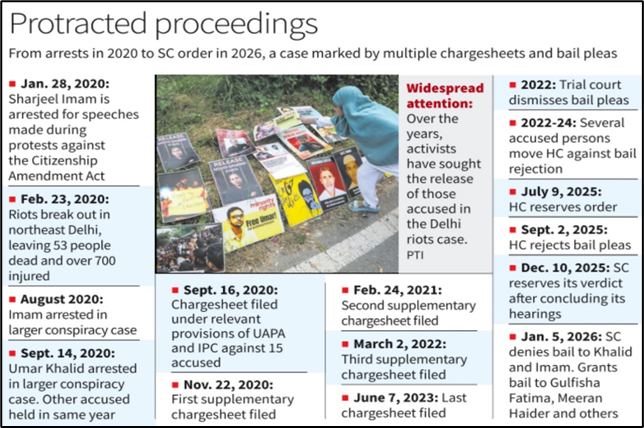

The Supreme Court of India granted bail to five of the seven accused in the 2020 Northeast Delhi riots case but denied relief to Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam. The Court held that the accused did not stand on equal footing, creating a hierarchy of culpability by distinguishing alleged principal planners from those with subsidiary or facilitative roles, even though all faced similar charges.

All accused are booked under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, along with the Arms Act and other penal provisions.

Central to the ruling are two issues: what constitutes a “terrorist act” and who determines it, and whether prolonged pre-trial incarceration is justified under anti-terror law. Beyond immediate bail outcomes, the order endorses an expansive interpretation of “terrorist act”, with implications for future UAPA cases.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Hierarchy of Roles’ in the Alleged Conspiracy

- How the Law Defines a ‘Terrorist Act’?

- Prolonged Incarceration and the Bail Question

Hierarchy of Roles’ in the Alleged Conspiracy

- The Supreme Court of India centred its bail decision on an individualised assessment of culpability, holding that the accused did not occupy the same position within the alleged conspiracy.

- The Court noted a clear hierarchy of roles, rather than treating all accused as equally culpable.

- Principal Accused: Alleged Masterminds

- For Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam, the Court found that prosecution material placed them at the level of conceptualisation, direction, orchestration, and mobilisation.

- They were described as “ideological drivers” and “masterminds”, allegedly responsible for strategising the transformation of protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act into disruptive chakka jams aimed at paralysing Delhi.

- The allegations suggested a central and directive role.

- Co-Accused Granted Bail: Peripheral Roles

- In contrast, the five accused granted bail were characterised as “local-level facilitators” or “site-level executors”.

- Their roles were termed derivative, indicating that they acted on instructions from higher levels of the alleged conspiracy rather than shaping it.

- The Court held that continued incarceration of these minor participants would be disproportionate, especially since the investigation was complete and the trial had seen significant delays.

How the Law Defines a ‘Terrorist Act’?

- Section 15 of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) defines a terrorist act as one carried out with intent to threaten India’s unity, integrity, security, economic security, or sovereignty, or to strike terror among people.

- The provision lists methods such as bombs, explosives, firearms, or inflammable substances, and also adds a broader clause—“or any other means”.

- The prosecution argued that an alleged “chakka jam” (road blockade) planned by the accused could fall under “any other means”, even if it did not involve conventional weapons, because of its intended impact and consequences.

- Defence’s Stand: Protest Is Not Terror

- Defence Counsel contended that road blockades are a legitimate democratic protest.

- Since Section 15 primarily refers to violent methods, he argued that “any other means” should be read narrowly to include only other violent means.

- Supreme Court’s View

- Rejecting the defence claim that the acts were mere political dissent, the Court accepted the prosecution’s view that sustained choking of arterial roads and systemic disruption of civic life can amount to calibrated acts threatening India’s unity and integrity.

- When such blockades are planned, synchronised, and timed with international events—such as the Donald Trump visit in 2020—they may prima facie fall within the definition of a terrorist act.

- The Court emphasised that the focus is not just on the weapon used, but on the design, intent, and effect of the act.

- Impact on Bail Under Section 43D(5)

- Under Section 43D(5) of the UAPA, bail is barred if accusations appear prima facie true.

- Applying this, the Court found that witness statements, chats, and meeting records established a prima facie conspiracy against Khalid and Sharjeel Imam.

- As a result, the statutory bar on bail operated fully against them.

Prolonged Incarceration and the Bail Question

- All appellants highlighted their long custody since 2020, with the trial still at the charge-framing stage.

- They relied on the Union of India v. K A Najeeb ruling, where the Supreme Court of India held that constitutional courts may grant bail under UAPA if there is no likelihood of a speedy trial, to protect Article 21 rights to life and liberty.

- SC’s Clarification on K.A. Najeeb

- The Court clarified that K.A. Najeeb is not a mechanical rule.

- Delay does not automatically override statutory bail bars; it acts as a trigger for heightened judicial scrutiny, not a “trump card.”

- The Court noted the voluminous record—over 1,000 documents and 835 witnesses—and procedural objections by the defence, holding that the delay cannot be attributed solely to the prosecution.

- The Court held that delay must be weighed against the gravity of the offence and the role of the accused.

- For alleged “masterminds” Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam, their conspiratorial centrality meant the statutory bar on bail prevailed despite delay.

- For co-accused characterised as facilitators with limited logistical or local roles, continued custody was deemed punitive.

- As they lacked the autonomous capacity to affect the trial, the balance tilted in favour of liberty.